Health care alone cannot counter the effects of an inadequate education.

More education means better health—in part because more education brings betters jobs, improved access to health insurance, and higher earnings that can help pay for medical expenses and a healthier lifestyle. Conversely, people with less education tend to have more challenges accessing health services—lower rates of health insurance coverage and less money to afford copayments and prescription drugs; they are also more likely to live in low-income neighborhoods with limited access to primary care providers.1

Will improved access to health care remove the health disadvantage that exists for people with less education? Will health care reform make high school dropouts as healthy as college graduates?

Not necessarily. Health care is necessary but not sufficient for improved health; in fact, health care accounts for only about 10–20% of health outcomes, according to some experts.2 Having access to good doctors and medicines is certainly important. And health care has a bigger impact for people with limited education than for those with more education,3 but access to health care by itself doesn’t eliminate the relationship between education and health.

People with fewer years of education have worse health than those with more education—even when they have the same access to health care.

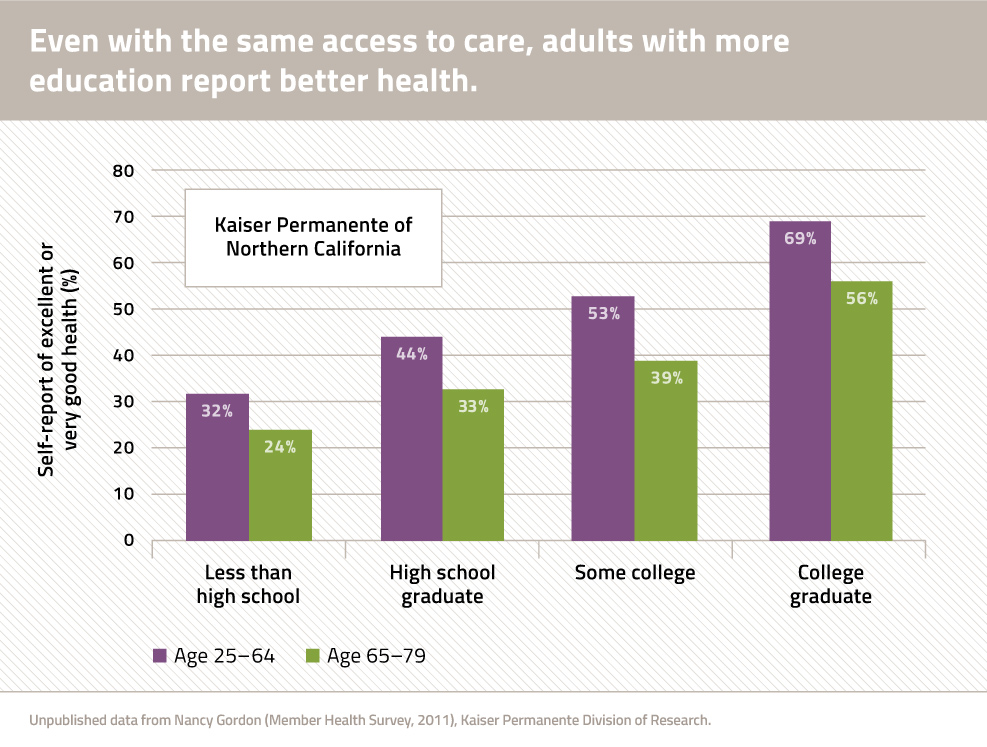

Consider data from Kaiser Permanente, one of the nation's oldest health systems, where all members of the plan have access to a similar level of care and network of providers. In a 2011 survey of members of Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, 69 percent of adults aged 25–64 with a college education described their health as "very good" or "excellent," compared to only 32 percent of those lacking a high school diploma (Figure 1).

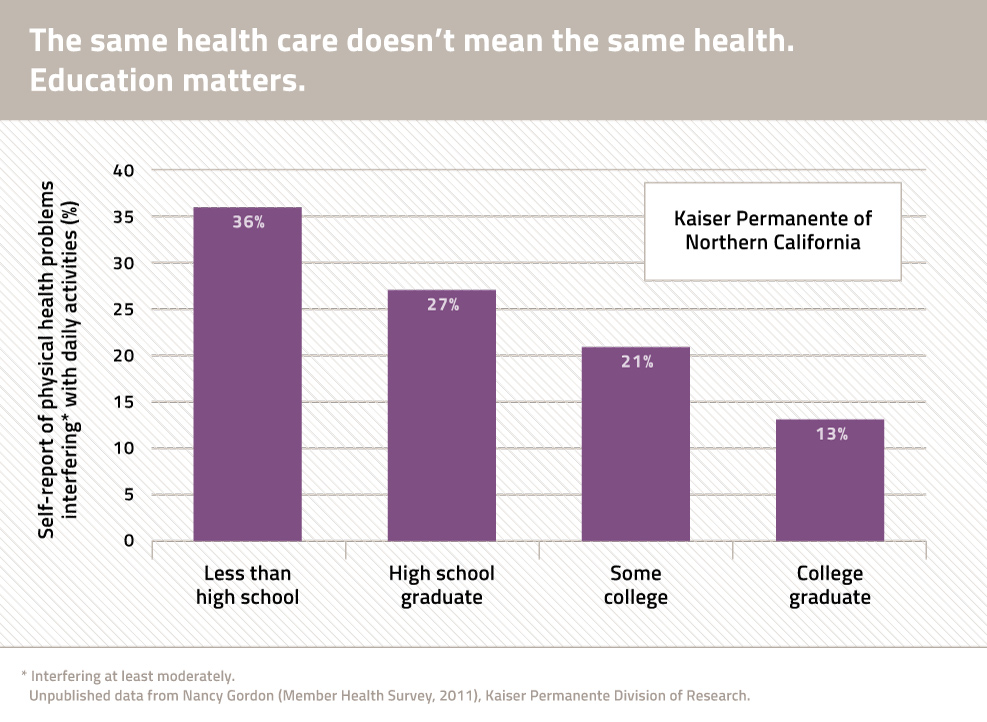

A similar trend is found among Kaiser members reporting physical health problems that interfere with daily activities: among adults aged 25–64, such physical health problems were reported by 36 percent of those with less than a high school education, but by only 13 percent of college graduates (Figure 2).

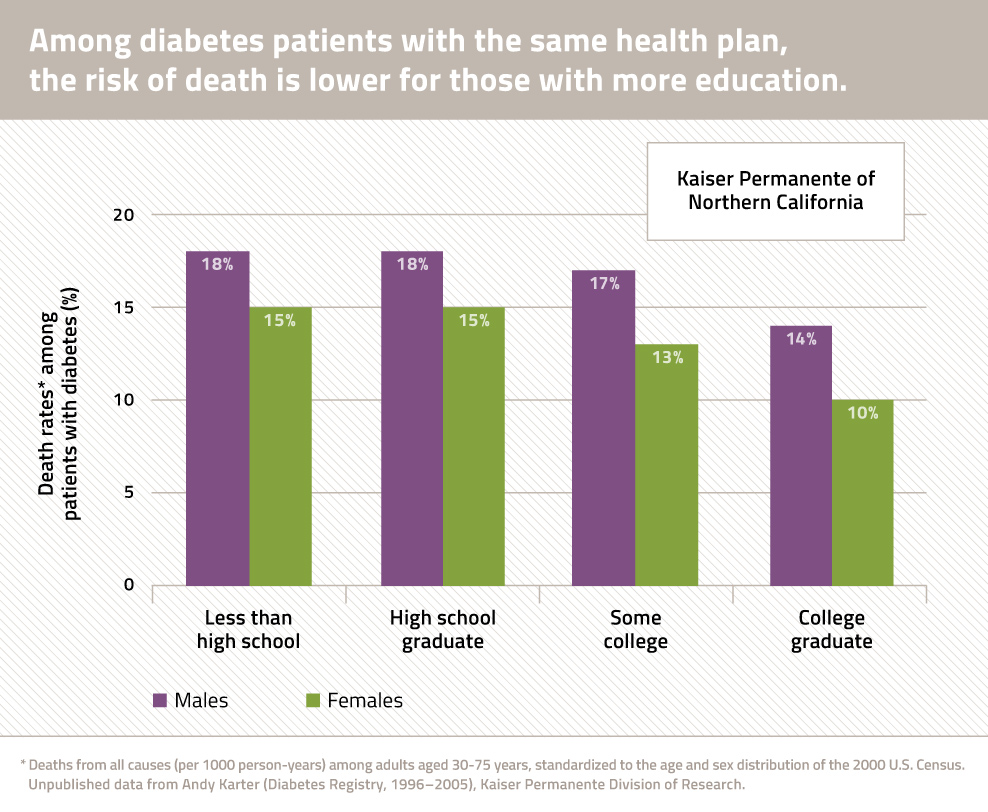

And it’s not true just for self-reports of problems—it’s also true for verifiable health outcomes, like mortality. For example, Kaiser data also show that the risk of death is lower among diabetes patients with more education (Figure 3), despite the fact that members at all education levels have access to the same health system for diabetes care. The Kaiser data offer a reminder that medical care is not everything: people with less education lack access to other resources (financial resources, community resources such as access to healthy food and others) that affect the management of diabetes and its progression to early death.

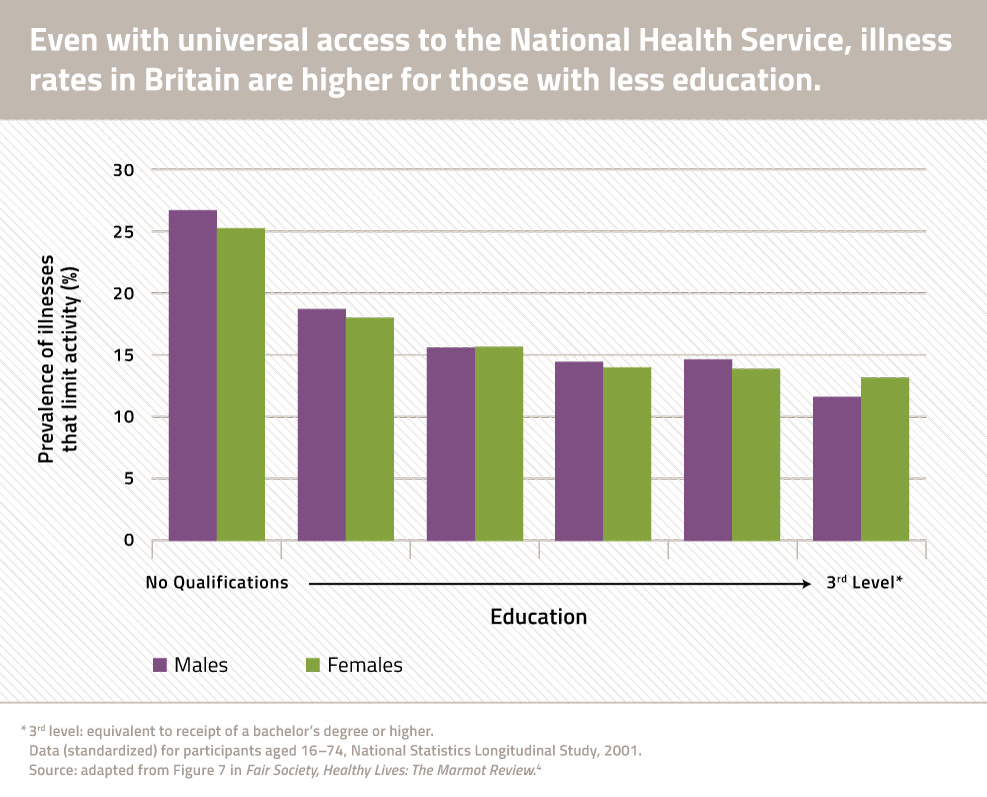

Even in countries where the entire population has access to a single health system, this same pattern is seen. For example, in the United Kingdom, where there is universal access to the National Health Service, illness rates climb for people with less education (Figure 4).4

What’s the takeaway?

Health care is necessary

Our nation needs to improve access to quality health care for the disadvantaged, including adopting reforms that widen access to health insurance coverage, improve the quality, and reduce health disparities.

But it’s not sufficient

Eliminating the adverse health consequences of a limited education will require other policies that target factors outside of health care that cause people with less education to experience greater illness despite access to health care.

Reforms are needed to improve access to a good education—better education from early childhood through college—but also to address related problems: diplomas alone will not solve everything. See our issue brief about the factors outside of education—from neighborhood conditions to job quality—that cause poor health among people with less education. Health care reform must be accompanied by changes in social and economic policies that are a “win-win”: creating economic opportunity for families while also saving lives (and costs) from medical illnesses.

Notes

- Centers for Disease Control, Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2010 BRFSS Data. Accessed 2-14-14 at http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/data_tools.htm

- Booske BC, Athens JK, Kindig DA, Park H, Remington PL. Different Perspectives for Assigning Weights to Determinants of Health. County Health Rankings Working Paper, 2010. Accessed 8-8-14 at https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/sites/default/files/differentPerspectivesForAssigningWeightsToDeterminantsOfHealth.pdf

- Zimmerman E, Woolf SH. Understanding the relationship between education and health. Discussion paper for Roundtable on Population Health, Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences, June 2014.

- Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England post-2010. Fair Society, Healthy Lives. The Marmot Review: Executive Summary. Accessed 8-29-14 at https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review