Americans with fewer years of education have poorer health and shorter lives, and that has never been more true than today. In fact, since the 1990s, life expectancy has decreased for people without a high school education, and especially white women.

Education is important not only for higher paying jobs and economic productivity, but also for saving lives and saving dollars.

Saving lives

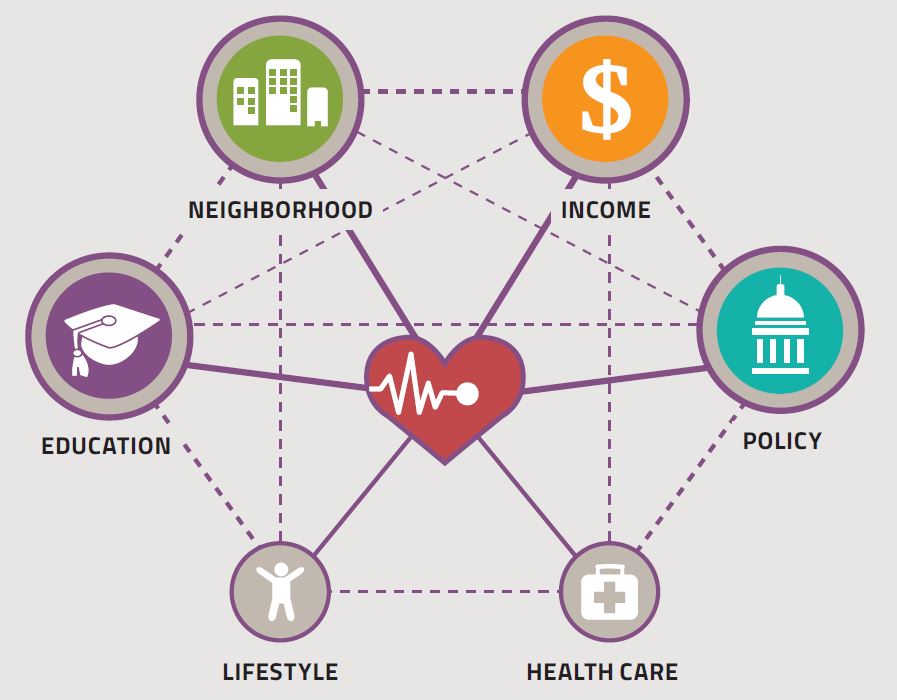

Policies that set kids up for success—in education and life generally—are smart strategies for reducing the prevalence of chronic diseases, such as diabetes and heart disease. More education leads to higher earnings that can provide access to healthy food, safer homes, and better health care. And policies in communities can help put children on track for better health and prosperity by strengthening schools, job opportunities, economic growth, safe and affordable housing, and transportation.

Saving dollars

Medical care is important, but actions outside of health care—education, jobs, and economic growth—may be the best way to stem spiraling health care costs ("bend the cost curve"). Disinvesting in education not only makes U.S. businesses less competitive in a global marketplace built on science and technology, but can also increase health care costs in the long run.

"Saving" money by cutting vital "non-health" programs can cost more in the end. We don’t help ourselves by creating a sicker population and workforce that require more expensive medical care.

Now, more than ever, people with less education face a serious health disadvantage

- Shorter lives: Americans with less education are—now, more than ever—dying earlier than their peers. Between 1990 and 2008, the life expectancy gap between the most and least educated Americans grew from 13 to 14 years among males and from 8 to 10 years among females. The gap has been widening since the 1960s.1

- Worse health: Americans with less education are—now, more than ever—more likely to have major diseases, such as heart disease and diabetes. By 2011, the prevalence of diabetes had reached 15 percent for adults without a high school education, compared with 7 percent for college graduates.10

- More risk factors: Those with less education are increasingly more likely to have risk factors that predict disease, such as smoking and obesity. By 2011, smoking was reported by 27 percent of people without a high school diploma or GED but by only 8 percent of those with a Bachelor’s degree.10

- Greater disability: Americans with less education are more likely to have diminished physical abilities for health reasons or to be disabled.

Americans without a high school diploma are at greatest risk

- Death rates are climbing: Adults with fewer than 12 years of education have been dying sooner since the 1990s. While overall life expectancy has generally increased, it has decreased for whites with fewer than 12 years of education, especially white women. Among whites with less than 12 years of education, life expectancy at age 25 fell by more than three years for men and by more than five years for women between 1990 and 2008.1

- Mortality trends for white women have reversed: Life expectancy increased for other Americans but has fallen for whites with fewer than 12 years of education, especially white women. Among whites with less than 12 years of education, life expectancy at age 25 fell from 47.0 to 43.6 years for males and from 54.5 to 49.2 years for females.1

Compared to those with a college education, Americans with less education:

- Die earlier: At age 25, U.S. adults without a high school diploma can expect to die 9 years sooner than college graduates.

- Live with greater illness: Adults with less education are more likely to report diabetes and heart disease and to have worse health.

- Generate higher medical care costs: The growing percentage of Americans in poor health intensifies demands on the health care system and fuels the rising costs of health care.

- Are less productive at work: A good education is important to work productivity on many levels, not just in cognitive skills but also in performing basic everyday tasks.

Education and workforce productivity for U.S. businesses: along with higher rates of disease, Americans without a high school education have dramatically higher rates of physical disabilities, such as inability to climb steps, stand, stoop, or lift large or heavy objects. [See Table 2] A good education is important to work productivity on many levels, not just in cognitive skills but in the basic measures of functional status.

- Experience more psychological distress: Stress is higher among poorly educated Americans, and this can have harmful biological effects.

- Have less healthy lifestyles: People with a high school education or less are more likely to have risk factors for disease—to smoke, to smoke while pregnant, to be physically inactive, to be obese, or to have children who are obese.10

What about race?

For generations in the United States, life expectancy has been higher among whites than blacks. But the differences in life expectancy by levels of education are now greater among whites than among people of color.

What's the cause? Why does education matter more to health now?

- In today's knowledge economy, education paves a path to good jobs: Completing more years of education confers health benefits after leaving school, such as better health insurance, access to medical care, and the resources to live a healthier lifestyle and to reside in healthier homes and neighborhoods.

- Early childhood shifts the odds for success—in health and education: Children who grow up in struggling, stressful homes or neighborhoods pay a double price: the living conditions disturb their education, and stress and other life conditions can cause lasting biological harms and cause youth to take up unhealthy or risky behaviors, such as smoking or violence.

Connect the dots

Education matters to health, and so do the conditions in neighborhoods and communities that harm the health of young children, trigger unhealthy or risky behaviors, and undermine the success of students and schools. Policies that address early child care, housing, transportation, food security, unemployment, and economic development are important to both education and health.

References

- Olshansky SJ, Antonucci T, Berkman L, et al. Differences in life expectancy due to race and educational differences are widening, and many may not catch up. Health Aff. 2012;31(8):1803-1813.

- Feldman JJ, Makuc DM, Kleinman JC, Cornoni-Huntley J. National trends in educational differentials in mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 1989 May;129(5):919-33.

- Pappas G, Queen S, Hadden W, Fisher G. The increasing disparity in mortality between socioeconomic groups in the United States, 1960 and 1986. N Engl J Med. 1993 Jul 8;329(2):103-9.

- Crimmins EM, Saito Y. Trends in healthy life expectancy in the United States, 1970-1990: gender, racial, and educational differences. Soc Sci Med. 2001 Jun;52(11):1629-41.

- Steenland K, Henley J, Thun M. All-cause and cause-specific death rates by educational status for two million people in two American Cancer Society cohorts, 1959-1996. Am J Epidemiol. 2002 Jul 1;156(1):11-21.

- Jemal A, Ward E, Anderson RN, Murray T, Thun MJ. Widening of socioeconomic inequalities in U.S. death rates, 1993-2001. PLoS One. 2008 May 14;3(5):e2181.

- Meara ER, Richards S, Cutler DM. The gap gets bigger: changes in mortality and life expectancy, by education, 1981-2000. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008 Mar-Apr;27(2):350-60.

- Congressional Budget Office. Growing Disparities in Life Expectancy. Economic and Budget Issue Brief. April 17, 2008.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2011: With Special Feature on Socioeconomic Status and Health. Hyattsville, MD. 2012.

- Schiller JS, Lucas JW, Peregoy JA. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2011. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 10(256). 2012.

- Marmot M, Ryff CD, Bumpass LL, Shipley M, Marks NF. Social inequalities in health: next questions and converging evidence. Soc Sci Med. 1997 Mar;44(6):901-10.

- Goldman D, Smith JP. The increasing value of education to health. Soc Sci Med. 2011 May;72(10):1728-37.

- Begier B, Li W, Maduro G. Life expectancy among non-high school graduates. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013 Apr;32(4):822.

- Preston SH, Elo IT. Are educational differentials in adult mortality increasing in the United States? J Aging Health. 1995 Nov;7(4):476-96.

- Montez JK, Zajacova A. Trends in mortality risk by education level and cause of death among US White women from 1986 to 2006. Am J Public Health. 2013 Mar;103(3):473-9.

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Gender and the health benefits of education. The Sociological Quarterly 2010; 51:1–19.

- Thurston RC, Kubzansky LD, Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Is the association between socioeconomic position and coronary heart disease stronger in women than in men? Am J Epidemiol. 2005 Jul 1;162(1):57-65.

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Sex differences in the effect of education on depression: resource multiplication or resource substitution? Soc Sci Med. 2006 Sep;63(5):1400-13.

- Ross CE, Masters RK, Hummer RA. Education and the gender gaps in health and mortality. DemoFigurey. 2012 Nov;49(4):1157-83.

- Woolf SH, Aron L, eds. U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Panel on Understanding Cross-National Health Differences Among High-Income Countries. National Research Council, Committee on Population, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, and Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2013.

- Kindig DA, Cheng ER. Even as mortality fell in most US counties, female mortality nonetheless rose in 42.8 percent of counties from 1992 to 2006. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013 Mar;32(3):451-8.

- Rogers RG, Everett BG, Zajacova A, Hummer RA. Educational degrees and adult mortality risk in the United States. BiodemoFigurey Soc Biol. 2010;56(1):80-99.

- Braveman P, Egerter S. Overcoming obstacles to health: report from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to the Commission to Build a Healthier America. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2008.

- Afxenfiou D, Kutasovic P. Does College Education Pay? Evidence from the NLSY – 79 Data. Contemporary Issues in Education Research [serial online]. January 2010;3 (1):119-126. Available from: Education Research Complete, Ipswich, MA. Accessed September 19, 2013.

- Nightingale D, Fix M. Economic and Labor Market Trends. Future of Children [serial online]. Summer 2004 2004;14(2):49-59. Available from: Education Research Complete, Ipswich, MA. Accessed September 17, 2013.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics Staff. A Profile of the Working Poor, 2011. BLS Reports. http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpswp2011.pdf. Published April, 2013. Accessed September 17, 2013.

- Carnevale AP, Jayasundera T, Cheah B. The college advantage: Weathering the economic storm. 2012:52. http://search.proquest.com/docview/1140131519?accountid=14780.

- Theodos B, Bednarzik R. Earnings mobility and low-wage workers in the United States. Monthly Labor Review. 2006:129(7):34-47. http://search.proquest.com/docview/235756014?accountid=14780.

- Issacs JB, Sawhill IV, Haskins R. Getting Ahead or Losing Ground: Economic Mobility in America. Economic Mobility Project. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 2008.

- Messacar D, Oreopoulos P. Staying in School: A Proposal for Raising High-School Graduation Rates. Issues in Science & Technology [serial online]. Winter2013 2013;29(2);55-61. Available from: Education Research Complete, Ipswich, MA. Accessed September 19, 2013.

- Conti G, Heckman JJ. Understanding the early origins of the education-health gradient: A framework that can also be applied to analyze gene-environment interactions. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2010;5(5):585-605.

- Zajacova A. Education, gender, and mortality: Does schooling have the same effect on mortality for men and women in the US? Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(8):2176-2190.

- Zajacova A, Hummer RA. Gender differences in education effects on all-cause mortality for white and black adults in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(4):529-537.

- Backlund E, Sorlie PD, Johnson NJ. A comparison of the relationship of education and income with mortality; the national longitudinal mortality study. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(10):1373-1384.

- Montez J, Hummer R, Hayward M. Educational attainment and adult mortality in the United States: A systematic analysis of functional form. DemoFigurey. 2012:49(1):315-336.

- Glenn ND, Weaver CN. Eduction’s effects on psychological well-being. The Public Opinion Quarterly. 1981:45(1):22-39.

Notes

- They also found that those with 0 to 8 years of education experienced decreases in the length of healthy life, causing educational differentials in healthy life expectancy to widen over time.

- Among adults, the increase in obesity was largest for men with at least some college and for women with at least some college or a Bachelor’s degree or higher, resulting in a narrowing of the education gradient in adult obesity.9

- Montez and Zajacova found that the gradient had not changed significantly for some causes of death, but had for others. The gradient increased—for lung cancer, cerebrovascular disease, chronic lower respiratory disease, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease. Death rates for heart disease fell for all women. Earlier modeling studies yielded mixed results on the influence of education on mortality among women.19, 32, 33

- Researchers have documented discrete health states associated with each stage of education: high school education but no diploma, high school diploma but no college, college education but no degree, and college degree.34, 35

- Survey data from the 1990s found that depression decreased more steeply for women than for men as the level of education increased. The gender gap in depression largely disappeared among persons with a college degree or higher.18 Earlier research from the 1970s described a link between education and markers of happiness, excitement in life, subjective health, and satisfaction with community—particularly among white women.36 [See Figure 15]

- Children also perform better in school when they are healthy. Although this “reverse causality” can explain some of the observed association between education and health, it does not account for the poor health outcomes that occur among adults who previously obtained a limited education.