Americans with more education live longer, healthier lives than those with fewer years of schooling (see Issue Brief #1). But why does education matter so much to health? The links are complex—and tied closely to income and to the skills and opportunities that people have to lead healthy lives in their communities.

How are health and education linked? There are three main connections:1

- Education can create opportunities for better health

- Poor health can put educational attainment at risk (reverse causality)

- Conditions throughout people’s lives—beginning in early childhood—can affect both health and education

This issue brief, created with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, provides an overview of what research shows about the links between education and health alongside the perspectives of residents of a disadvantaged urban community in Richmond, Virginia. These community researchers, members of our partnership, collaborate regularly with the Center on Society and Health’s research and policy activities to help us more fully understand the “real life” connections between community life and health outcomes.

1. The Health Benefits of Education

Income and Resources

“Being educated now means getting better employment, teaching our kids to be successful and just making a difference in, just in everyday life.” —Brenda

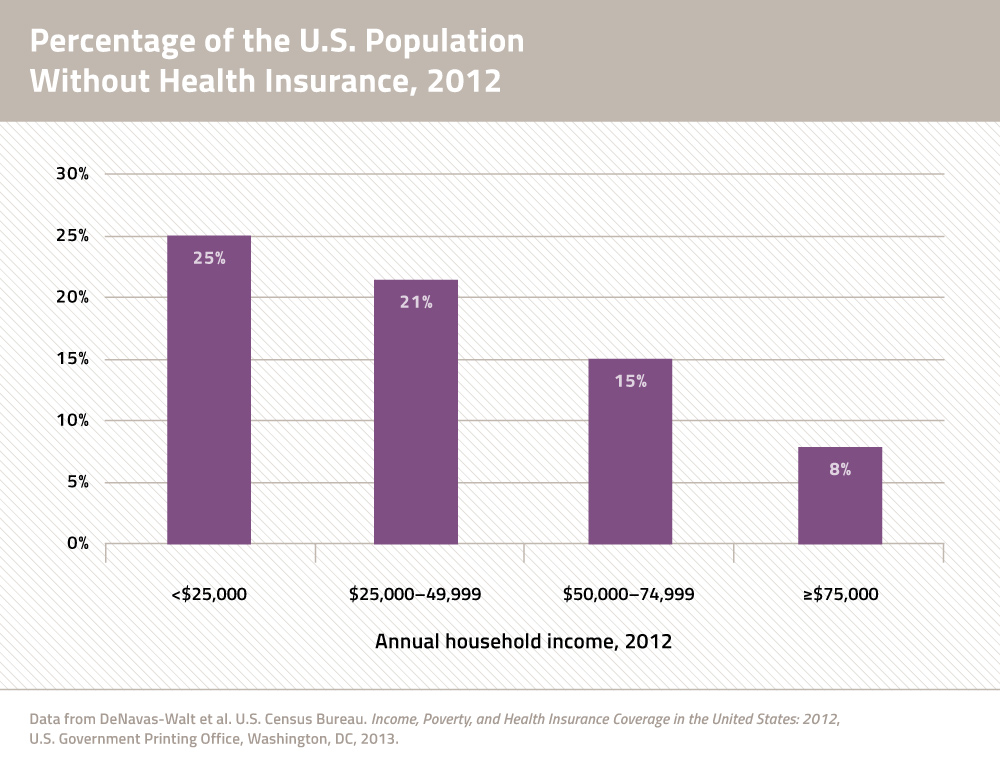

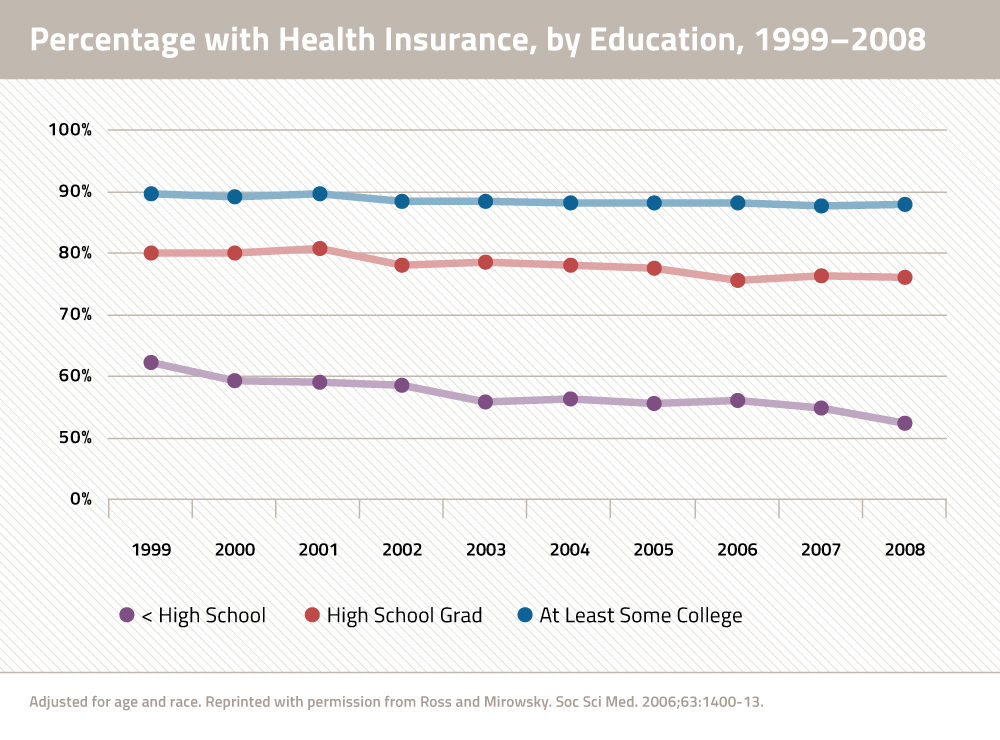

Better jobs: In today’s knowledge economy, an applicant with more education is more likely to be employed and land a job that provides health-promoting benefits such as health insurance, paid leave, and retirement.5 Conversely, people with less education are more likely to work in high-risk occupations with few benefits.

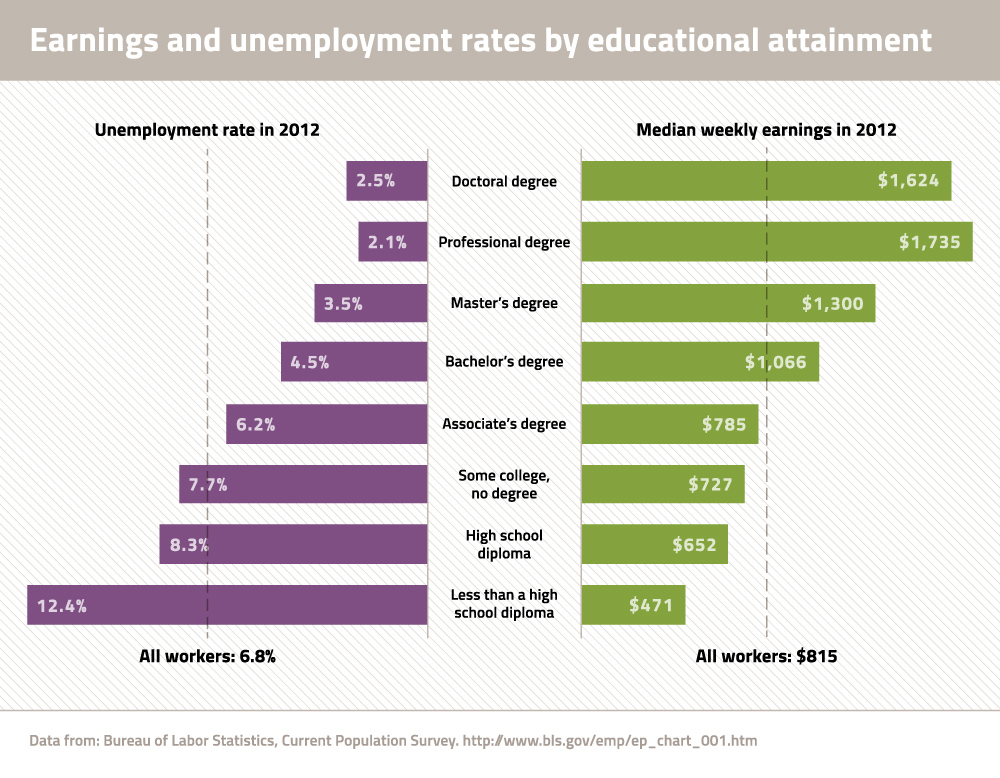

Higher earnings: Income has a major effect on health and workers with more education tend to earn more money.2 In 2012, the median wage for college graduates was more than twice that of high school dropouts and more than one and a half times higher than that of high school graduates.6 Read More

“Definitely having a good education and a good paying job can relieve a lot of mental stress.”

—Chimere

Resources for good health: Families with higher incomes can more easily purchase healthy foods, have time to exercise regularly, and pay for health services and transportation. Conversely, the job insecurity, low wages, and lack of assets associated with less education can make individuals and families more vulnerable during hard times—which can lead to poor nutrition, unstable housing, and unmet medical needs. Read More

Social and Psychological Benefits

“So through school, we learn how to socially engage with other classmates. We learn how to engage with our teachers. How we speak to others and how we allow that to grow as we get older allows us to learn how to ask those questions when we're working within the healthcare system, when we're working with our doctor to understand what is going on with us.”

—Chanel

Reduced stress: People with more education—and thus higher incomes—are often spared the health-harming stresses that accompany prolonged social and economic hardship. Those with less education often have fewer resources (e.g., social support, sense of control over life, and high self-esteem) to buffer the effects of stress. Read More

Social and psychological skills: Education in school and other learning opportunities outside the classroom build skills and foster traits that are important throughout life and may be important to health, such as conscientiousness, perseverance, a sense of personal control, flexibility, the capacity for negotiation, and the ability to form relationships and establish social networks. These skills can help with a variety of life’s challenges—from work to family life—and with managing one’s health and navigating the health care system. Read More

Social networks: Educated adults tend to have larger social networks—and these connections bring access to financial, psychological, and emotional resources that may help reduce hardship and stress and improve health. Read More

“Being able to advocate and ask for what you want, helps to facilitate a healthier lifestyle. … If it's needing your community to have green spaces, have a park, a playground, have better trails within the community, advocating for that will help.”

—Chanel

Health Behaviors

Knowledge and skills: In addition to being prepared for better jobs, people with more education are more likely to learn about healthy behaviors. Educated patients may be more able to understand their health needs, follow instructions, advocate for themselves and their families, and communicate effectively with health providers.21 Read More

Healthier Neighborhoods

“Poor neighborhoods oftentimes lead to poor schools. Poor schools lead to poor education. Poor education oftentimes leads to poor work. Poor work puts you right back into the poor neighborhood. It's a vicious cycle that happens in communities, especially inner cities.” —Albert

Lower income and fewer resources mean that people with less education are more likely to live in low-income neighborhoods that lack the resources for good health. These neighborhoods are often economically marginalized and segregated and have more risk factors for poor health such as:

- Less access to supermarkets or other sources of healthy food and an oversupply of fast food restaurants and outlets that promote unhealthy foods.25

“If the best thing that you see in the neighborhood is a drug dealer, then that becomes your goal. If the best thing you see in your neighborhood is working a 9 to 5, then that becomes your goal. But if you see the doctors and the lawyers, if you see the teachers and the professors, then that becomes your goal.” —Marco

“It's a lot of things going on [in this community], a lot of challenges. It's just hard sometimes to try and get people to come together, as one, just so we can solve the problem.” —Toni

- Less green space, such as sidewalks and parks to encourage outdoor physical activity and walking or cycling to work or school.

- Rural and low-income areas, which are more populated by people with less education, often suffer from shortages of primary care physicians and other health care providers and facilities.

- Higher crime rates, exposing residents to greater risk of trauma and deaths from violence and the stress of living in unsafe neighborhoods. People with less education, particularly males, are more likely to be incarcerated, which carries its own public health risks.

- Fewer high-quality schools, often because public schools are poorly resourced by low property taxes. Low-resourced schools have greater difficulty offering attractive teacher salaries or properly maintaining buildings and supplies.

- Fewer jobs, which can exacerbate the economic hardship and poor health that is common for people with less education.

- Higher levels of toxins, such as air and water pollution, hazardous waste, pesticides, andindustrial chemicals.27

- Less effective political influence to advocate for community needs, resulting in a persistent cycle of disadvantage.

2. Poor Health That Affects Education (Reverse Causality)

“Things that happen in the home can definitely affect a child being able to even concentrate in the classroom. … If you're hungry, you can't learn with your belly growling. … If you’re worried about your mom being safe while you're at school, you're not going to be able to pay attention.” —Chimere

The relationship between education and health is never a simple one. Poor health not only results from lower educational attainment, it can also cause educational setbacks and interfere with schooling.

For example, children with asthma and other chronic illnesses may experience recurrent absences and difficulty concentrating in class.28 Disabilities can also affect school performance due to difficulties with vision, hearing, attention, behavior, absenteeism, or cognitive skills. Read More

3. Conditions Throughout the Life Course—Beginning in Early Childhood—That Affect Both Health and Education

A third way that education can be linked to health is by exposure to conditions, beginning in early childhood, which can affect both education and health. Throughout life, conditions at home, socioeconomic status, and other contextual factors can create stress, cause illness, and deprive individuals and families of resources for success in school, the workplace, and healthy living. Read More

What about social policy?

Social policy—decisions about jobs, the economy, education reform, etc.—is an important driver of educational outcomes AND affects all of the factors described in this brief. For example, underperforming schools and discrimination affect not only educational outcomes but also economic success, the social environment, personal behaviors, and access to quality health care. Social policy affects the education system itself but, in addition, individuals with low educational attainment and fewer resources are more vulnerable to social policy decisions that affect access to health care, eligibility for aid, and support services.

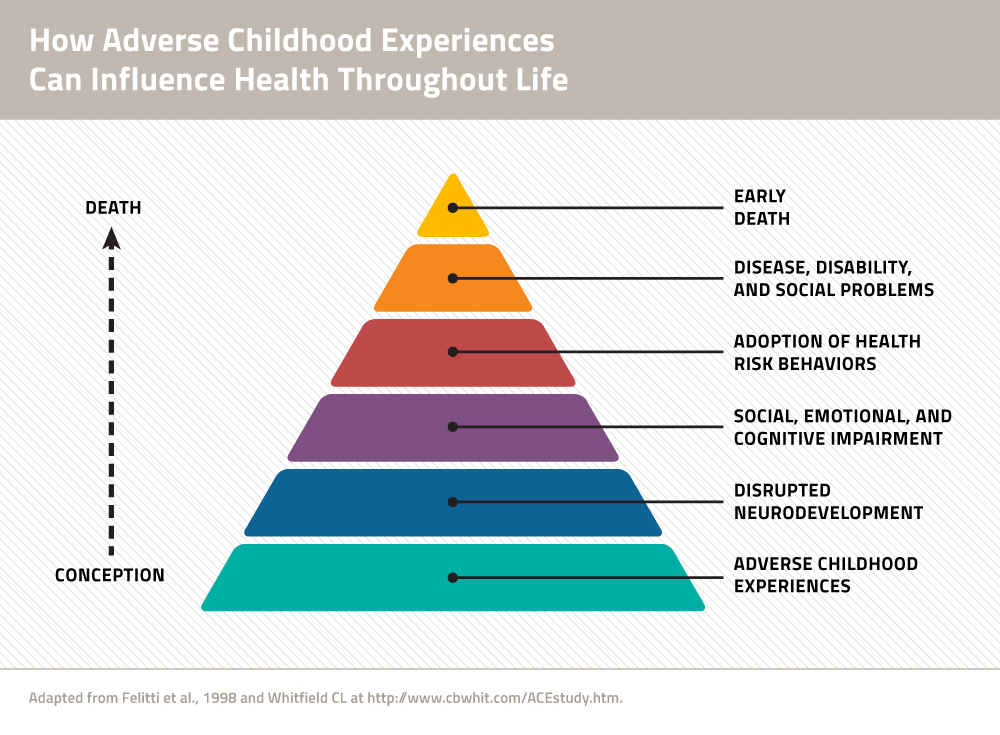

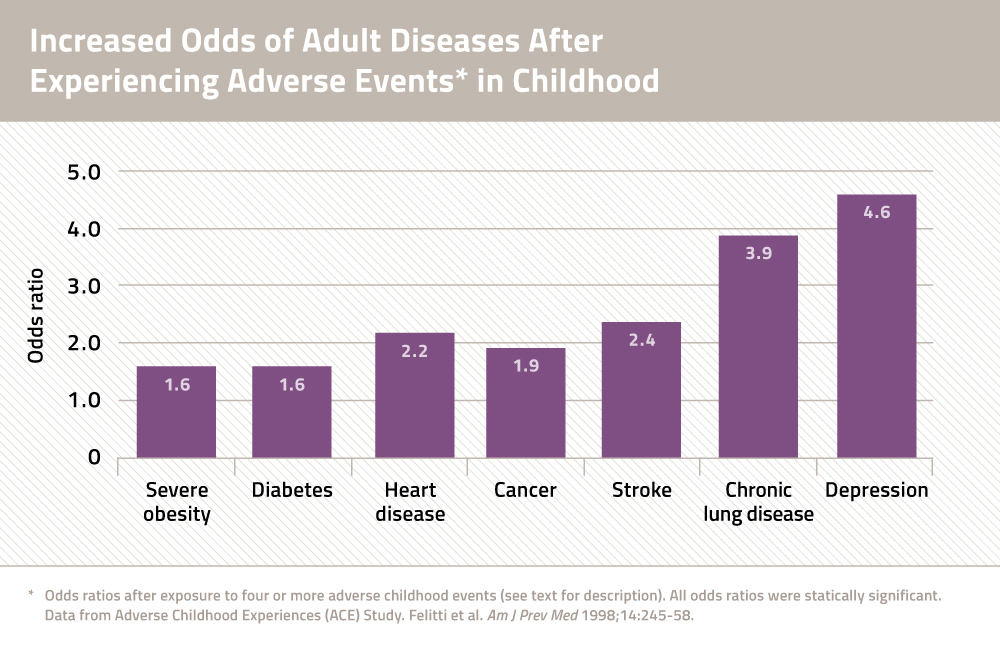

A growing body of research suggests that chronic exposure of infants and toddlers to stressors—what experts call “adverse childhood experiences”—can affect brain development and disturb the child’s endocrine and immune systems, causing biological changes that increase the risk of heart disease and other conditions later in life (see Graphic 1). For example:

“The connection that I will say between education and health would be a healthy mind produces a healthy person. A motivated mind produces a motivated person. A curious mind produces a curious person. When you have those things it drives you to want to know more, to want to have more, to want to inquire more. And when you want more, you will get more. You know where the mind goes the person follows… and that includes health.” —Marco

- The adverse effects of stress on the developing brain and on behavior can affect performance in school and explain setbacks in education. Thus, the correlation between lower educational attainment and illness that is later observed among adults may have as much to do with the seeds of illnessand disability that are planted before children ever reach school age as witheducation itself.

- Children exposed to stress may also be drawn to unhealthy behaviors—such as smoking or unhealthy eating—during adolescence, the age when adult habits are often first established.

What about individual characteristics?

Characteristics of individuals and families are important in the relationship between education and health. Race, gender, age, disability and other personal characteristics often affect educational opportunities and success in school (see Issue Brief #1). Discrimination and racism have multiple links to education and health. Racial segregation reduces educational and job opportunities51 and is associated with worse health outcomes.52, 53

How does education impact health in your community?

The Center on Society and Health (CSH) worked with members of Engaging Richmond, a community-academic partnership that included residents of the East End, a disadvantaged neighborhood of Richmond, Virginia. This inquiry into the links between education and health was a pilot study to learn how individuals could add to our understanding of this complex issue using the lens of their own experiences.

What does your community have to say about the links between education and health – or other health disparities? Learn more about community research partnerships and community engagement:

References

- Cutler D., and Lleras-Muney A. Education and Health. In: Anthony J. Culyer (ed.), Encyclopedia of Health Economics, Vol 1. San Diego: Elsevier; 2014. pp. 232-45.

- Olshansky SJ, et al. Differences in life expectancy due to race and educational differences are widening, and many may not catch up. Health Aff 2012;31:1803-13.

- Goldman D, Smith JP. The increasing value of education to health. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:1728-37.

- Montez JK, Berkman LF. Trends in the educational gradient of mortality among US adults aged 45 to 84 years: bringing regional context into the explanation. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e82-90.

- Baum S, Ma J, Payea K. Education Pays 2013: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society. College Board, 2013.

- Current Population Survey, U.S. Department of Labor, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accessed 4/9/14 at http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_table_001.htm.

- Julian TA and Kominski RA. Education and Synthetic Work- Life Earnings Estimates. American Community Survey Reports, ACS-14. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, 2011.

- Sobolewski JM, Amato PR. Economic hardship in the family of origin and children’s psychological well-being in adulthood. J Marriage Fam 2005;67:141-56.

- Centers for Disease Control, Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2010 BRFSS Data. Accessed Feb 14, 2014 at http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/data_tools.htm

- Steele CB, et al. Colorectal Cancer Incidence and Screening – United States, 2008 and 2010. CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report — United States, 2013. Centers for Disease Control. MMWR 2013;62(3):53-60.

- Mcewen BS, Stellar E. Stress and the individual: mechanisms leading to disease. Arch Int Med 1993;153:2093-101.

- Karlamangla AS, et al. Reduction in allostatic load in older adults is associated with lower all-cause mortality risk. Psychosom Med 2006;68:500–7.

- Ross CE, Wu CL. The links between education and health. Am Soc Rev 1995;60:719-45.

- Roberts BW, et al. The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspect Psychol Sci 2007;2:313-45.

- Heckman JJ, Kautz T. Hard evidence on soft skills. Labour Economics 2012;19:451-64.

- Berkman LF. The role of social relations in health promotion. Psychosom Med 1995;57:245-54.

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Refining the association between education and health: the effects of quantity, credential, and selectivity. Demography 1999;36:445-60.

- Kaplan GA, et al. Social functioning and overall mortality: Prospective evidence from the Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Epidemiology 1994;5:495-500.

- Seeman TE. Social ties and health: the benefits of social integration. AEP 1996;6:442-51.

- Sum A, et al. The Consequences of Dropping Out of High School: Joblessness and Jailing for High School Dropouts and the High Cost for Taxpayers. Center for Labor Market Studies, Northeastern University, Boston, 2009.

- Goldman DP, Smith JP. Can patient self-management help explain the SES health gradient? Proc Natl Acad Sci 2002;10929–10934.

- Spandorfer JM, et al. Comprehension of discharge instructions by patients in an urban emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 1995;25:71-4.

- Williams MV, et al. Inadequate literacy is a barrier to asthma knowledge and self-care. Chest 1998;114:1008-15.

- Berkman ND, et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:97-107.

- Ver Ploeg M, et al. Access to Affordable and Nutritious Food—Measuring and Understanding Food Deserts and Their Consequences: Report to Congress. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2009.

- Grimm KA, et al. Access to Health Food Retailers—Unites States, 2011. CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report — United States, 2013. Centers for Disease Control. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62: 20-26.

- Brulle RJ, Pellow DN. Environmental justice: human health and environmental inequalities. Annu Rev Public Health 2006;27:103-24.

- Basch CE. Healthier Students Are Better Learners: A Missing Link in School Reforms to Close the Achievement Gap. New York: Columbia University, 2010.

- Case A, et al. The lasting impact of childhood health and circumstance. J Health Econ 2005;24:365-89.

- Suhrcke M, de Paz Nieves C. The impact of health and health behaviours on educational outcomes in high-income countries: a review of the evidence. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2011.

- Barbaresi WJ, et al. Long-term school outcomes for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a population-based perspective. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2007;28:265-73.

- Behrman JR, Rosenzweig MR. 2004. Returns to birthweight. Rev Econ Statistics 2004;86:586-601.

- Black SE. et al. From the Cradle to the Labor Market? The Effect of Birth Weight on Adult Outcomes. NBER Working Papers 11796, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2005.

- Avchen RN, et al. Birth weight and school-age disabilities: a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol 2002;154:895-901.

- Chapman DA, et al. Public health approach to the study of mental retardation. Am J Ment Retard 2008;113:102-16.

- Conti G, Heckman JJ. Understanding the early origins of the education-health gradient. Perspect Psychol Sci 2010;5:585-605.

- Denhem SA. Social-emotional competence as support for school readiness: what is it and how do we assess It? Early Educ Dev 2006;17:57-89.

- Williams Shanks TR, Robinson C. Assets, economic opportunity and toxic stress: a framework for understanding child and educational outcomes. Econ Educ Rev 2013;33:154-70.

- Currie J. Healthy, wealthy, and wise: socioeconomic status, poor health in childhood, and human capital development. J Econ Lit 2009,47:87–122.

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhood they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychol Bull 2000;126:309-337.

- Barnett WS, Belfield CR. Early childhood development and social mobility. Future Child 2006;16:73-98.

- Hackman DA, et al. Socioeconomic status and the brain: mechanistic insights from human and animal research. Nat Rev Neurosci 2010;11:651-9.

- Gottesman II, Hanson DR. Human development: biological and genetic processes. Annu Rev Psychol 2005;56:263-86.

- Shonkoff JP, Phillips DA, Eds. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Child Development. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2000.

- Felitti VJ, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14:245-58.

- McEwen BS. Brain on stress: how the social environment gets under the skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2012;109 Suppl 2:17180-5

- Zhang TY, Meaney MJ. Epigenetics and the environmental regulation of the genome and its function. Annu Rev Psychol 2010;61:439-66.

- Egerter S, et al. Education and Health. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2011.

- Mistry KB, et al. A new framework for childhood health promotion: the role of policies and programs in building capacity and foundations of early childhood health. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1688-96.

- Liu Y, et al. Relationship between adverse childhood experiences and unemployment among adults from five U.S. states. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013;48:357-69.

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. J Behav Med 2009;32(1), 20–47.

- White K, Borrell LN. Racial/ethnic residential segregation: Framing the context of health risk and health disparities. Health Place 2011;18: 438-48.

- Smedley BD et al., eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2003.